Brickmaking in Kent

(originally extracted from “Chalk Mining & Associated Industries of Frindsbury”)

A hand-made yellow stock brick showing the initials “FBC” (Frindsbury Brickfield Company) on the frog. A great many of the older buildings in the district are built from these.

Up to the 19th Century, many inhabitants of Kent lived in wooden houses since bricks were an expensive commodity that only the rich could afford. The presence of large areas of forest made wood a cheap alternative and most windmills used to have a saw attachment to produce planks for this purpose. Even today houses are still seen with the traditional clapperboard walls. Over the years, however, the forests of Kent and Sussex shrunk as wood was consumed by the Wealden iron industry and for shipbuilding. In the 19th century, the repealing of a tax on bricks and the growing scarcity of cheap timber began to make brick a more popular building material and one that had become commonplace by the end of the Century.

Before this, builders tended to make their own bricks on site and some large estates had their own small brickworks for private use. There was insufficient demand to produce bricks on a commercial scale. This situation changed dramatically with the expansion of the Naval Dockyard at Chatham and its associated military barracks and defence works. Suddenly, there was a great demand for bricks and the vast surface deposits of brickearth in the area began to be exploited on a commercial scale. Even more important, a massive house re-building programme began in London and the Medway and East Kent area were ideally placed to serve this capacious market. Not only were the brickfields situated next to the River Medway but there was an existing barge trade down the Medway and up the Thames. Bricks could thus be produced and transported right into the heart of London at very competitive rates.

Numerous brickfields sprang up all over the Kent area and the trade became so lucrative that, in 1880, the massive firm of Eastwoods Co Ltd was formed from the merger of five of larger operations. Their influence was great since they operated their own fleet of barges and probably controlled the price of bricks for the whole area. Vast areas of agricultural land disappeared as a result of brickfields but the great advantage of this industry was that there was no lasting effect. Once the brickearth had all been removed and the brickfield abandoned, it left a flat area of land which exposed the underlying Thanet Sand. This could then be reclaimed for cultivation as it was ideal for orchards. Many farmers cashed in on the trend by leasing out fields for brickworks or even working them themselves for a number of years. They could then plant orchards on the site, having made far more money in the intervening period than the original fields could have produced. A feature of the area today is the

sight of flat fields which are up to 6ft below road level, this is often the only remaining indication of their previous use for brickmaking. It is an interesting thought that many of London's Victorian houses were originally part of fields from this area!

The most popular type of brick produced in this area was the yellow Kent Stock Brick. This colour was obtained by including 10-17% of chalk in the mixture and by careful firing of the bricks. Some chalk or sand was included in normal mixtures anyway to prevent cracking or shrinkage but the larger proportion of chalk was necessary to obtain the right colour. It was also much in demand because of its unique durability in the polluted environment of Victorian London. The famous London smogs were mainly due to vast quantities of acidic gases such as Sulphur Dioxide being released from factory chimneys. These produced a chemical reaction on the face of the Kent Stock brick that produced a very hard surface glaze which was extremely water-resistant, although it caused the colour to darken. Modern practice to sand blast bricks to recover the original colour is not such a good idea since it reduces these qualities of water-resistance.

At this stage, it is worth looking in some detail at actual working methods of the brickfields. To begin with, about 1ft of top soil had to be removed ("uncallowed") to expose the brickearth beneath. The term brickearth is a general one applied to deposits of varying consistency which were usually all referred to as clay. Clay digging was normally done in winter and the diggers were paid on a piece rate for the amount of clay equivalent to 1,000 bricks. It is estimated that a volume of clay measuring 44ft x 8ft x 6ft deep would make about 33,000 bricks. Dug clay was left exposed in heaps for a time to allow it to weather before being mixed into a slurry with water in a Washmill.

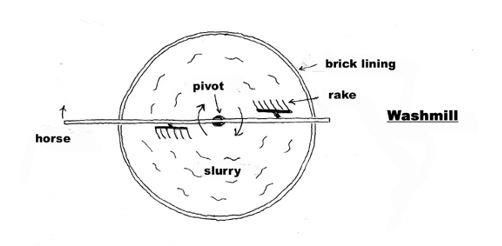

This device was usually a sunken circular brick-lined pit about 4ft deep and up to 15ft wide. In later years, some brickfields used open-topped metal tanks for this. A vertical pivot in the middle supported a horizontal beam that was turned by a horse in the early days until they were replaced by mechanical means. To each side of the beam was attached a device similar to a large rake which, as it rotated, broke up the clay placed in the washmill and mixed it into slurry with the water that had also been added. At this stage, the correct proportion of chalk was added if Kent Stocks were being produced and the rakes crushed the chalk which was incorporated into the slurry. At some brickfields, a small amount of river mud was added at this stage to improve the mixture and at the Crayford Brickworks they even added rags! These were brought from London on the barges and picked into threads by women and children. The purpose of this was to provide more combustible material in the bricks during firing. As soon as slurry was the right consistency, a sluice built into the washmill wall was opened and the slurry was allowed to flow into pipes or wooden launders.

This device was usually a sunken circular brick-lined pit about 4ft deep and up to 15ft wide. In later years, some brickfields used open-topped metal tanks for this. A vertical pivot in the middle supported a horizontal beam that was turned by a horse in the early days until they were replaced by mechanical means. To each side of the beam was attached a device similar to a large rake which, as it rotated, broke up the clay placed in the washmill and mixed it into slurry with the water that had also been added. At this stage, the correct proportion of chalk was added if Kent Stocks were being produced and the rakes crushed the chalk which was incorporated into the slurry. At some brickfields, a small amount of river mud was added at this stage to improve the mixture and at the Crayford Brickworks they even added rags! These were brought from London on the barges and picked into threads by women and children. The purpose of this was to provide more combustible material in the bricks during firing. As soon as slurry was the right consistency, a sluice built into the washmill wall was opened and the slurry was allowed to flow into pipes or wooden launders.

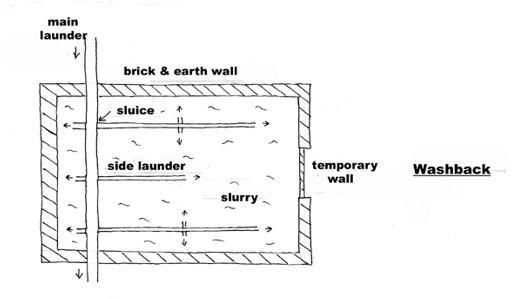

The slurry was then laundered to features called Washbacks, which were settling ponds.These were square enclosures surrounded by brick walls up to 6ft high which were banked with soil on the outside to provide extra strength. There was a small gap left in the front wall which was boarded until the slurry had dried. A brickfield normally had at least 3 washbacks in line and an amount of slurry was placed into each in turn. About 2 days were allowed for the water to drain out before more slurry was added, this process being repeated until the washback was full. The mixture was then allowed to dry until it had reached the right consistency for brickmaking. Since many of the subsequent operations were carried out in the open, brickmaking was dependant on the weather and the season lasted from April to October. Men were laid off during the winter, apart from a few who were involved in clay digging.

The slurry was then laundered to features called Washbacks, which were settling ponds.These were square enclosures surrounded by brick walls up to 6ft high which were banked with soil on the outside to provide extra strength. There was a small gap left in the front wall which was boarded until the slurry had dried. A brickfield normally had at least 3 washbacks in line and an amount of slurry was placed into each in turn. About 2 days were allowed for the water to drain out before more slurry was added, this process being repeated until the washback was full. The mixture was then allowed to dry until it had reached the right consistency for brickmaking. Since many of the subsequent operations were carried out in the open, brickmaking was dependant on the weather and the season lasted from April to October. Men were laid off during the winter, apart from a few who were involved in clay digging.

Excavating a washback in one of the larger Eastwood brickworks in the 1900s. The slurry launders can be seen in the background.

Excavating a washback in one of the larger Eastwood brickworks in the 1900s. The slurry launders can be seen in the background.

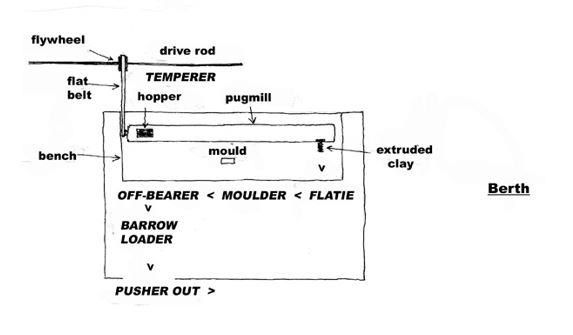

The actual making of the bricks was done by gangs of persons who were often family units including women and children as labourers. Each gang operated from a "berth", which was a sited in front of the washbacks, the ratio normally being 2 berths for every 3 washbacks. Inside the berth was a bench, at the back of which was sited a "pugmill", which was a 6ft long narrow cylinder containing an Archimedes screw. Clay was placed in one end and the action of the screw carried it to the other end, in the process cutting it up and making it pliable. The berths were placed in line so that their pugmills could be operated from a flat belt off a mechanically—operated

drive shaft. As soon as operations were ready to commence, the access to the washback was unboarded, exposing the clay mixture which was of a stiff consistency.

The first member of the gang was called a "Temperer" and his job was to cut the clay out of the washback. This was a strenuous job and he used a tool called a "Large Cuckle", which was a three-pronged fork with a sharp blade across the bottom. Anyone who has dug in clay will know that it tends to stick to spades so this was an ideal device to cut and carry clay without having a large surface area for clay to stick to. The temperer filled a barrow which he wheeled up a plankway into the back the berth. He emptied the clay into a hopper which fed it into the pugmill already described. Since the team was paid on piece rate, it was important for the temperer to keep the pugmill filled and this job could only be undertaken by strong, fit men.

At the other end of the pugmill, a small aperture extruded the clay and this is where the “Flatie” worked. He used a bow-shaped knife called a “Small Cuckle” to cut off enough of the extruded clay to make one brick. This was rolled in sand to take away some of the stickiness and handed to the "Moulder". The moulder had the most important job and was in overall charge of the gang. He had a rectangular mould, the inside of which he sprinkled with sand each time to prevent the clay sticking its sides. This fitted snugly over a separate base attached the bench and the clay was thrown into the mould with some force so it would completely fill it. The moulder then used a wooden scraper called a "Stricker" to level the clay and removed the mould from the base. Some bricks had an indentation on one side called a "Frog", which contained the initials of the brickworks, and the impression for this was inbuilt into the mould base. Tapping the mould on the bench, the newly-formed brick (called a green brick) was removed and the moulder prepared for the next one. The green bricks were picked up by the "Off Bearer", who stacked them on the floor next to the bench. Since the moulder’s job was quite strenuous, due to the necessity of throwing clay into the mould with some force, the moulder and off bearer changed places at regular intervals to keep the work flow moving.

The "Barrow Loader" stacked the green bricks onto a long, flat wooden barrow. This took 30 bricks, 15 to a side, and weighed 210 lbs when full. Since the green brick still contained a lot of moisture, it weighed a lot more than the completed product. The "Pusher Out" took the loaded barrows and wheeled these to the "Hacks" to dry out, each gang having their own hack to enable the brickworks to calculate the payment. A hack consisted of 1,000 bricks stacked 7 courses high on wooden planks, with wooden end boards and caps to keep the bricks dry.

The state of the industry can be appreciated from the price per 1,000 bricks paid to the brickmaking gangs. During the boom time prior to 1900, it was 4 shillings but this dropped to 2/10d after competition began to bite. The shares paid to the members of the gang reflected the importance of their job and out of the 2/10d they received the following :-

- Moulder - 7d

- Off Bearer - 7d

- Temperer - 7d

- Flatie - 5d

- Pusher Out - 4d

- Barrow Loader - 3d

This left 1d which was known as "Pence Money" and was kept to be shared out as an end of season bonus. To earn enough to keep them over winter, the gangs would work all the hours of daylight and an average gang could produce 38,000 bricks per week, although some were known to make up to 50,000.

A brickmaking gang at Rainham in 1890 standing in front of a hack. Note the moulds, large cuckle and brick barrow.

A brickmaking gang at Rainham in 1890 standing in front of a hack. Note the moulds, large cuckle and brick barrow.

After about 5 weeks, the dried bricks (now known as "white bricks") were up to 2 lbs lighter and were ready for firing. Only the larger concerns had proper kilns and the traditional method of firing was by making a "cowl", sometimes known as a "clamp". Gangs of 4-5 men called "Crowders" would load the white bricks onto crowding barrows, which held 70 at a time, and took them to where the cowl was to be built. A cowl had 750-800 bricks which were laid on edge, 5-6” apart, to form channels, into which the fuel was placed. Ascending rows narrowed towards the top for stability, up to a maximum of height of 32 bricks. The outside was covered with a layer of rejected bricks to retain the heat. The fuel was lit from either end through gaps left at the bottom of the cowl and left to burn for 4-5 weeks.

The fuel used was known as "Rough Stuff" or "London Mixture" and consisted of partly burnt coal and ashes. It was obtained by sifting out (or "scrying") household rubbish, some of which was brought back from London on the empty barges. Large piles of this rubbish was left for about a year to allow the vegetable matter to rot away and brickworks must have been very popular with people living nearby! The sifting to extract ashes was carried out in winter and represented a vital, albeit unpleasant, income to a lucky few of the brickworkers who would otherwise have been laid off. The larger lumps were used in cowls and some of the fine ash was added to the slurry so that it helped to fuse the bricks during firing. This material was still used by a few local brickworks up to the 1960s until the advent of smokeless fuels caused the ashes to contain insufficient combustible material. The current fuel used in the large kilns is now coal dust.

Once the cowl was fired, a man called a “Skintler" removed alternate bricks from the top of the outside layer and replaced these at an angle to allow air to circulate. During the course of firing, all of the outside bricks were eventual criss-crossed to allow sufficient draught to keep the fire burning. At the centre of the cowl, the temperature reached 900 degrees Centigrade but this decreased towards the edges. When the firing was complete, a gang of 4 "Sorters" dismantled the cowl and sorted the bricks into 6 grades, their condition depending on their location in the cowl and how effectively the cowl had been fired :-

- First Stocks – yellow, used for facings

- Second Stocks - straw coloured, used for facings

- Third Stocks - orange, used for interior walls

- Roughs - brown and distorted, used for footings

- Burrs - black and fused into lumps, used for hardcore

- Chuffs - red and half-baked, rejected.

The brickfield obtained a better price for 1st and 2nd Stocks, thus the stacking and firing of the cowl was a skilful and important job in order to get as equal a temperature to the bricks as possible. The larger firms used permanent kilns and there were a number of technical advances in their design in order to attain a better proportion of saleable bricks. The earliest design was the Updraught Kiln (also called a Scotch Kiln) which was rectangular and open-topped with fire holes along the bottom. It was basically a permanent cowl which was filled with bricks and it allowed the hot gases to rise amongst them. The next development was the Downdraught Kiln, which was circular and about 15ft in diameter with a roof. Here the hot gases rose but were deflected back down onto the bricks, this being more efficient in fuel consumption. Closable ports in the roof allowed more fuel to be introduced during firing if necessary.

The Hoffmann Continuous Kiln was the first move towards mass production and was basically a series of downdraught kilns, connected in a circle or in a long rectangle. Each kiln had an access port to the next and, as soon as the first kiln was into its firing process, the heat would begin to fire the next one. The fires would thus burn around in sequence, allowing brickfields time to remove bricks from a completed firing and reload the kiln with green bricks ready for its turn. There was thus always an empty kiln ready to take green bricks so production was not delayed waiting for a firing to be completed. A kiln of this type is still in use at a brickworks in Rainham. The next development was the Long Continuous Kiln where bricks were stacked on flat wagons which were slowly passed through a chamber where hot gases could circulate around them.

The beginning of the decline of the local brick industry started in 1881 when a dark, shaly clay was discovered at Fletton near Peterborough. Some 5% of its weight was tar oil and it was found that bricks made from this material needed very little fuel since they were almost self-firing. By 1908, there was a great deal of competition anyway amongst brickmakers as more concrete was being used in buildings and the Fletton brickmakers combined to drop the price to 8/6d per 1,000 (in 1903 the local price had been 29/-). They could do this because their self-firing bricks could be produced very cheaply in great numbers and they were able to undercut the local product, even with the costs of transport. As a result, the smaller and less efficient local brickworks began to close and a temporary building boom a few years later was tragically cut short by the 1st World War. After the war, trade began to pick up again as result of a Government-aided building programme but, by 1929, a slump had set in to the whole industry. Many brickworks closed at this time, never to reopen.