The Sons of Colonel James

Frederick Honeyball

The last two sons of an illustrious family spent their lives gambling and breaking speeding laws, but played a small role in developing new technology, They grew up among the gardens and orchards at Newgardens, Teynham, since the 1840s., It was all part of an idyllic childhood for the Honeyball boys. Martyn (right in the picture) and Lawrence (left in the picture) who were the sons of Colonel James Frederick Honeyball, a wealthy farmer and businessman, and his wife, Olympia.

The last two sons of an illustrious family spent their lives gambling and breaking speeding laws, but played a small role in developing new technology, They grew up among the gardens and orchards at Newgardens, Teynham, since the 1840s., It was all part of an idyllic childhood for the Honeyball boys. Martyn (right in the picture) and Lawrence (left in the picture) who were the sons of Colonel James Frederick Honeyball, a wealthy farmer and businessman, and his wife, Olympia.

Much has been written about the Colonel and his wife, who were pillars of the community of Teynham, entertaining illustrious guests such as the Duke of York, the future George VI, as well as welcoming schoolchildren and village clubs and societies. But the strange and tangled tale of what the boys went on to do is also interesting.

James Frederick Martyn Hearne Honeyball, who preferred to be called Martyn, travelled the world, moved to Australia, ditched the family name and was instrumental in changing the way we tax our cars.

Lawrence Ley-Kempthorne Honeyball registered an early patent for pre-war radar and radio technology, came up with an idea for reusing air raid sirens after the war, and then gambled away the family fortune as a London socialite.

Neither married and they were the last of the line. The engagement of Martyn to Rachel, only child of Dr and Mrs Irby Webster, of The Parsonage, Rainham, was announced in 1925, but the wedding never went ahead and she died in 1929.

Martyn served in the RAF as a pilot officer until 1920, although it is unclear whether or not he flew. He had no other career, and when on his travels to Chile, Jamaica, New Zealand and Australia, he always went first class and gave his occupation as “None”.

He tired of life in Teynham, and by 1926 he was living in Tasmania, where, on 14 July, a legal notice shows his name change to J. F. Martyn Hearne. The local newspapers also show him committing an impressive string of driving offences, most of them for speeding.

His father had died in 1923, and although he maintained business interests in Tasmania, Martyn travelled home frequently, and usually gave his address as Newgardens.

He was back in Teynham by the 1930s, adding to his tally of driving offences around Kent and Sussex, but took out patent for improvements to the internal combustion engine in Australia in June, 1947.

And it was engines that sparked Martyn’s interest and greatest claim to fame. Since the earliest days of motoring, taxation rates in Britain had been based on the horsepower of a vehicle, using a complicated formula devised by the RAC, involving piston surface area, cylinder bore in inches and maximum piston speed. But as design and technology progressed in the 1920s and 1930s, engines were developing much more power than their RAC rating suggested.

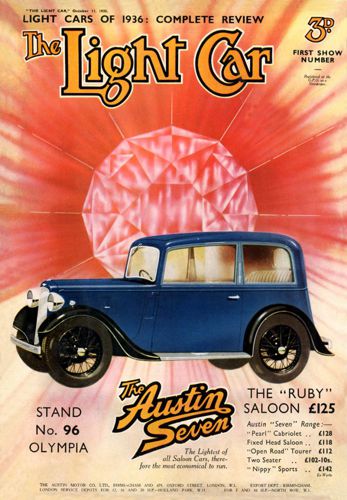

By 1924, the 747cc Austin Seven, named for its 7hp rating, was actually producing 10.5 brake horsepower, 50% more than its official rating. It became common for car- makers to include both the RAC tax horsepower and the actual output in model names, bringing us names such as the Alvis 12/70 and the Wolseley 14/60.

The 1935 Standard Flying Twelve (as shown) boasted a 1.6-litre engine, with aluminium head, and developed 44 brake horsepower, almost four times its RAC taxation rate.

Quite how Martyn Hearne became involved in the debate is uncertain, but in October, 1945, the East Kent Gazette reported that he had “proposed a scheme for the taxation of motor vehicles based on the literage capacity, which is claimed as being far more equitable than the current method”.

Wireless technology

Not only that, it was warmly welcomed by car company bosses, including those of Morris Motors, Rolls-Royce, Vauxhall and Armstrong Siddeley, and endorsed by the Automobile Association.

Modestly named by Martyn as the Hearne Litre Capacity Tax, it was indeed adopted by the government, and was the basis of the way we taxed vehicles for the next 70 or so years, until emissions became a more important part of the equation.

Lawrence followed his brother into the RAF in 1927, again on a short-service commission as a Pilot Officer with the General Duties Branch, which often indicates an intelligence role rather than flying.

But whatever his work, he seems to have developed an interest in wireless technology. In June, 1935, he registered what he claimed was a first UK patent in what became known as radar, having worked on the use of wireless beams for direction finding and location of obstacles. According to a 1947 East Kent Gazette report, at the outbreak of war he had handed over all the secrets in connection with his scientific discoveries “quite free of charge” and continued to work to improve the efficiency of his apparatus without any sort of fee or reward.

There is no doubt that he registered a patent relating to the new technology, but it was not the first, nor was it the invention of the system that was to play such a vital part in Britain’s war in the air and at sea. Prompted by rumours that the Germans had produced a “death ray”, in 1934 the Air Ministry had asked scientist Sir Robert Watson-Watt to investigate. The Air Ministry had already offered £1,000 to anyone who could demonstrate a ray that could kill a sheep 100 yards away. Watson-Watt concluded that such a device was highly unlikely, but wrote a memo saying that he had turned his attention to “the difficult, but less unpromising, problem of radio-detection as opposed to radio-destruction”.

Hostile aircraft.

Watson-Watt and his assistant made some calculations and applied some of the same techniques he used in his earlier atmospheric work.

In February, 1935, Watson- Watt demonstrated the first practical radio system for detecting aircraft. The Air Ministry was impressed and, in April, Watson-Watt received a patent for the system and funding for further development. Soon, Watson- Watt was using pulsed radio waves to detect aircraft up to 80 miles away and by the outbreak of war; Britain had Chain Home stations around the coast, many in Kent, to detect hostile aircraft.

Lawrence Honeyball’s work was recognised after the war. National Archive patents records show that he was rewarded by the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors, formed to recompense members of the public who had valid claims of ownership of copyright to inventions and processes used for the benefit of the country during the war.

Perhaps less successful after the war was his idea for using redundant air raid sirens. In May, 1947, the East Kent Gazette reported that a practical use for sirens which had been standing idle since the war had been suggested by Lawrence.

For a few shillings, he submits, they “could be converted and used for ventilating buildings or as exhaust fans in hop kilns where electricity supplies are available. Moreover, the odious sound associated with the operation of air-raid sirens would not be heard.”

There are no records of sirens being used in this way. Almost all stayed in position, and by the 1950s were seen as a vital part of the Cold War early-warning system that was in place until as late as 1992.

Not only the sirens fell quiet after the war. The two brothers who had shown such enterprise in their early careers slipped out of the spotlight. Martyn continued to travel the world. He had some business interests in Australia, and lived for a while in Tasmania, but carried on travelling. He ended up in the Channel Islands, living for a while in St Peter’s Port and died in the Princess Elizabeth Hospital, Guernsey, in 1962. He left no will.

Lawrence stayed in the UK and by the 1950s was gambling and moving in wealthy social circles in London. It has been claimed that his gambling bankrupted the family. He had been living at Newgardens, but after his mother’s death, stayed with the family of a cousin for a while. He died in 1968, again leaving no will, and is buried in Teynham churchyard.

After Olympia’s death in 1956, Newgardens had fallen into disrepair and was vandalised while her affairs were being sorted. Rumours at the time were that she took her own life after being bankrupted by Lawrence – or had been bitten by a snake in the garden.

Because all three had died intestate, it was not until 1972 that the financial tangle was sorted and probate granted. The house was demolished, and housing built on the site was named New Gardens Road – just around the corner from Honeyball Walk.

Adapted from an article by Crispin Whiting in Volume 42, No2 (March to April 2021) in Bygone Kent magazine (http://bygonekent.org.uk/) by kind permission of Christine Rayner