Richard Harrys, Henry VIII's Fruiterer, and Cherries

Richard Harrys, also spelt Harris, was born locally. A house called New Gardens in Conyer, a hamlet of Teynham, is claimed to have been his home. The story goes that when Harrys heard of Henry VIII's passion for cherries and some of the apples he had found growing in France, on one of his visits there, the Kent businessman went to the Continent himself and bought some trees which he brought back with him and planted them on land at Teynham. He 'fetched out of France a great store of graftes, especially pippins,” before which time there were no pippins in England. He fetched also out of the Lowe Countries 'cherrie grafts and Pear grafts of diverse sorts.'

The site chosen to establish the fruit orchards at Teynham was land stretching to 105 acres around the area of Oziers Farm and Newgardens, now Honeyball Walk. It was given to Harrys by the King for this purpose. In 1533 Richard Harrys, by then Henry Vlll's fruiterer, established what was probably England's first large fruit collection at Teynham. By the end of the century Harrys's collection had become 'the chief mother of all other orchards' in England.

Teynham is widely associated with the growing of cherries, which are said to have come originally-from Cerasus, a city of Pontus, a maritime town belonging to the Turks in Asia from whence it derived the present name of Cherry. Lucullus, a Roman General, brought them into Italy around 68 BC. They were first introduced into Britain about the year 53, in the reign of Nero, it is said via the Romans as many a Roman road had cherry trees along its length, sprouted, it is suggested, from stones spat out by marching legions. The Anglo-Saxons are said to have lost them and Richard Harrys to have re-imported them.

After the Romans left Britain, many of their agricultural skills left with them, but a small range of sweet cherry varieties continued to be cultivated here, especially in monasteries, which became hotbeds of horticultural learning. It is said that there were good native cherries around Norfolk which were known in the thirteenth century.

The fruits continued to be sold in medieval market. The ‘Forme of Cury’, the famous medieval cookbook published around 1390, contains two cherry-based recipes. One, ‘chyryse’, is a bread pudding with cherries and almonds. The second, ‘chireseye’ - a blend of crushed cherries, wine, butter, breadcrumbs and sugar.

One famous 15th century poem, ‘London Lickpenny’, telling of a poor man of Kent who goes to seek is fortune in the big city and see cherries on sale in the streets, includes a market trader’s call of: “Strabery rype, and chery in the ryse [‘on the branch’]”.

Also a folk song ‘Cherry Ripe’ written by the English poet Robert Herrick (1591 - 1574), Immortalises the following refrain

Cherry ripe, cherry ripe,

Ripe I cry,

Full and fair ones

Come and buy.

Cherry ripe

Cherry ripe,

Ripe I cry,

Full and fair ones

Come and buy.

As in France and Italy, it was the status of fruit as a princely luxury which was a main attraction. After Henry's split with Rome in 1534 he used every means at his disposal to proclaim his power and exalt the monarchy. Orchards, and fine gardens replete with fruit trees, were high on the list of palatial additions he financed out of the immense wealth derived from the dissolution of the monasteries.

It was documented in 'Reeve's Account of the Manor of Teynham, 1376, that cherries were grown in the service of the Church, quote: 'twenty pence as payment for cherries sent to the lord', The 'lord' being the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Royal example helped to stimulate consumption in fashionable circles, which in turn led to the establishment of new orchards to supply the metropolis. Tudor agriculture was shaking off its feudal ties and the new spirit of commercial enterprise provided the opportunity for men like Harrys to set up thriving businesses. His 105 acres, here at Teynham, became the basis of Kent's infant fruit industry and as the London market expanded, including that most famous of trading centres for Kentish produce - Borough Market. An increasing number of fruiterers seized the chance to buy or lease their own orchards., others began to travel down each year before harvest to purchase the prospective crops of cherries, pears, wardens (pears), medlars, pippins, and other apples, while they were still on the tree. Soon Kent could claim to be 'the garden of England’, Teynham the ‘home’ of the cherry orchard.

There is. an account of a cherry orchard of 32 acres in Kent which, in 1540, produced fruit that sold in these early days for £1000, which seems an enormous sum, as at .that time good land is stated to have let at one shilling (5 new pence) per acre. We can only reconcile our minds to this great price, from the deficiency of other fruits in this country and the splendour in which Henry VIII and his ministers lived.

When William Lambarde, a London lawyer and author of ‘A Perambulation of Kent’, who became a Kent Justice of the Peace, was travelling through the coastal area between Rochester and Canterbury in 1570, he found orchards of apples and gardens of cherries and “those of the most delicious and exquisite kindes that can be, no part or the realm (that I know) hath them in either such quantity and number or with such art and industry set and planted.”

A great expansion of the cherry growing industry took place during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries along the North Kent Down and the Faversham Fruit Belt was born. This area covered from Rochester to Canterbury with the deep loams of the Thanet sands chalk and brick earth. Cherries were shipped to the London markets via the Swale and Conyer Creek.

A great expansion of the cherry growing industry took place during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries along the North Kent Down and the Faversham Fruit Belt was born. This area covered from Rochester to Canterbury with the deep loams of the Thanet sands chalk and brick earth. Cherries were shipped to the London markets via the Swale and Conyer Creek.

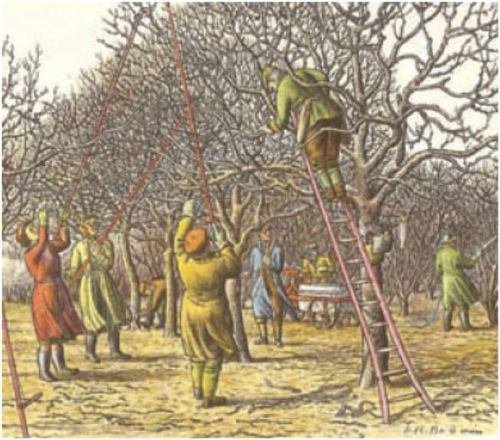

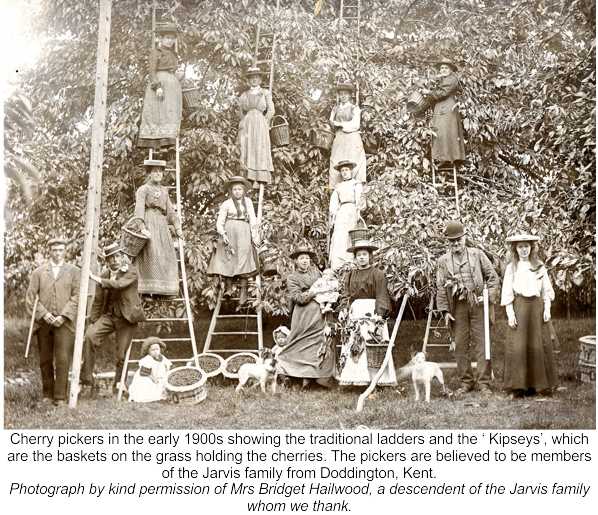

The cherry orchards in Kent grew to around 5,000 hectares, dramatically declining at the beginning of the 20th century to just 600. In more recent times however, we have gone from memories of H E Bates country, a dreamland of 1950s Kent, when children tucked bunches of cherries behind their ears and picnicked in orchards of cathedrals of standard cherry trees supporting 50ft ladders, to newly planted acres of smaller closely planted trees enclosed by metal frames covered with rain-proof plastic and netting at the sides to protect the fruit from its great enemy - birds. These bushy, high-yielding trees can be easily picked and covered for protection in the growing season. Sadly though there are very few cherry orchards left in Teynham, with areas of Richard Harrys’ orchards having been used for housing.