My Old Teynham

A couple of us boys earned quite a bit of money by picking up the old beer bottles that had been thrown away by the Londoners who went down to the coast by charabanc. We took them home, rinsed the dirt off them and took them back to the Bottle and Jug round the back of the Tavern to Elsie Bailey and her sister who ran it then. For some reason the half pint bottles were worth more than the pint or quart bottles, the smaller ones we got 4d for (1.5p) and the larger ones 2d. We sometimes got up to 30s. (£1.50p) which was almost as much as a week’s wages for a farm labourer. In those days you were not a man till you smoked and drank so with some of the money we bought ourselves some cigarettes, I seem to remember they were 4d for five or 8d for ten (approx 3.5p) and we were then only nine or ten years old!

Talking of the Tavern, Mr Gates, or Flimp as we called him, who was our headmaster at Teynham School, used to garage his car behind the pub. I don’t know how he got that name but I know he didn’t particularly like it. When we called after him one dark night, he chased us and we jumped down onto the railway line (before it was electrified) and came up by the bridge. The following day we were hauled up in front of the school as the main suspects. He knew how to swing a cane!!

I remember my first day at the old Teynham School, the infants' end. We hung our coats up and went down a step into Mrs Carpenter’s class, she was elderly by this time and actually taught my mother. She lived in the cottages that lay back below the old Brunswick Arms pub at Conyer and I believe she was well into her nineties when she died. Being wartime paper was at a premium so we used a slate with a wooden border and wrote with a slate pencil, when you had filled it up you rubbed it out with a damp cloth. After the war we used knibbed pens and blue ink, and very messy stuff it was to use. It came in stone pint bottles and most kids aspired to be an ‘Ink monitor’, that is to fill up the inkwells in the desks. Heating in the winter was from a coke filled potbelly stove in the centre of each room. We were still using the air raid shelters, which had been specially built, behind the school. We had to hold hands and file two deep from our classroom to the shelter. It was dark in them and they always smelt musty.

I was still at this school when Princess Elizabeth married and they travelled by train to Dover to sail on their honeymoon. The whole school lined up in the playing fields facing the railway with our Union Flags, for about an hour waiting for the ‘Golden Arrow’ special train to go through. I remember when it did come by with its royal flags crossed on the front, it was travelling at about 60m.p.h. and we didn’t see a thing. However since then having been in a royal guard and shortly to be present at an unveiling of a war memorial I shall have seen a lot more of them than I did then.

By the age of twelve, I with many other Teynham children caught a steam train every day to school at Faversham; we were issued with free season tickets. I don’t recall ever having the wrong type of leaves on the line; we were got to school come hell or high water. There were ‘first’ and 'third' class compartments and woe betide you if the guard caught you in a ‘first’ class seat. On foggy days they placed explosive percussion caps on the rails to warn the driver that he was approaching a signal or a station.

Most of us children at some time or other were in the choir at St Mary’s church; we had to attend every Sunday and sometimes twice. We are not deeply religious but most of us were christened and married there and many of those who were not spread throughout the world are buried there. This has been our church for many generations of our family over hundreds of years. Whatever the rules of the church say about Parish boundaries and wherever we may be this is still ‘our’ church and we still return for special occasions.

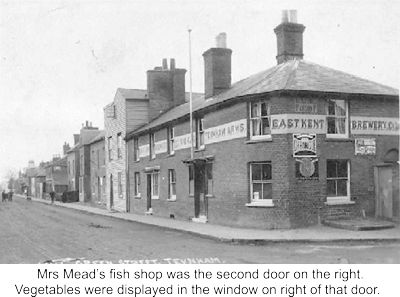

At 12 years of age I got a job at Mrs Mead's chip shop, where Crispins is now. I had to get up at 0530hrs and go with a sack barrow to meet the early morning paper train. The summer mornings were nice with the dawn chorus but after a heavy snowfall and crisp ice on the road it wasn’t so good. Dad used to save the rabbit skins or use felt to make us a pair of mittens for my hands. At the station I would pick up several boxes of frozen fish that had come down from London. This I took back to the shop, half a mile away and there I peeled a hundredweight of potatoes in an agitator before going to school. These were placed in a wooden half-barrel of water ready for the evening's frying. I would then go back in the evening and chip the potatoes and help with serving the fish and chips. I also worked Saturday mornings and for all this I got ten bob (ten shillings or 50p). Mrs Mead only had one eye and liked her drink. She would give me 6s (three florins) (30p) and send me to the Dover Castle to get a miniature whisky and half a Guinness. Half an hour later she would send me to The George with the same order and then another half hour later again to the Swan. She used to do this so that it wasn’t obvious to the village what she was drinking. She also told me not to let her partner, Mr Ward know. When Mr Ward did talk, which wasn’t very often, he was an interesting guy to talk to; he was in his eighties then and had been in Victoria’s Navy as a boy seaman.

At 12 years of age I got a job at Mrs Mead's chip shop, where Crispins is now. I had to get up at 0530hrs and go with a sack barrow to meet the early morning paper train. The summer mornings were nice with the dawn chorus but after a heavy snowfall and crisp ice on the road it wasn’t so good. Dad used to save the rabbit skins or use felt to make us a pair of mittens for my hands. At the station I would pick up several boxes of frozen fish that had come down from London. This I took back to the shop, half a mile away and there I peeled a hundredweight of potatoes in an agitator before going to school. These were placed in a wooden half-barrel of water ready for the evening's frying. I would then go back in the evening and chip the potatoes and help with serving the fish and chips. I also worked Saturday mornings and for all this I got ten bob (ten shillings or 50p). Mrs Mead only had one eye and liked her drink. She would give me 6s (three florins) (30p) and send me to the Dover Castle to get a miniature whisky and half a Guinness. Half an hour later she would send me to The George with the same order and then another half hour later again to the Swan. She used to do this so that it wasn’t obvious to the village what she was drinking. She also told me not to let her partner, Mr Ward know. When Mr Ward did talk, which wasn’t very often, he was an interesting guy to talk to; he was in his eighties then and had been in Victoria’s Navy as a boy seaman.

On the opposite corner of Teynham Lane to the shop was Brett’s garage and electric shop. He could charge your accumulator (wet acid battery) for your wireless (radio!) for 6d, just over two and halfpence. On the other side of the A2 was the ironmonger’s shop, there you could buy virtually anything, which was kept immaculately clean. We bought our paraffin for lamps and candles for power cuts there. During thunderstorms every stroke of lightening seemed to create a power cut which would last for several hours.

In the winter of 1953 we had the disastrous floods, the like of which had not been seen in living memory. All the marshes were flooded and Osiers stream was about three metres deep with dead fish and bloated cows and sheep floating in it. The water also went under the railway and flooded Hales’ meadow and Sandowns into what was the riverbed of the old Lynn; it was nearly two metres deep at the base of the Cliffs, that area sounded hollow underneath as if there were subterranean tunnels. The water reached as far as the low lying area by Teynham station and the Red Shed; there were railway sidings there then where they loaded all the fruit and hops. We played ‘hookey’ from school and went to Conyer where the Navy were blowing up huge sections of the seawall to let the water out when the tide was down. They then rushed to sand bag the holes up again before the tide came in. WWII Dukws (pronounced ducks - amphibious trucks) were used to rescue some stranded animals, but thousands were drowned.

The cause of the flooding was a combination of weather and tides that are luckily very rare. A very high tide in the North Sea had been held back by a very strong Southerly wind. This went cyclonic and swung round during the day to a Northerly, thence blowing water up round Scotland onto the first tide that had been held back, and then down the North Sea. A high pressure in the North and a low in the South made the situation worse. Communications were not so well organised then as they are today and nobody from the North thought to inform the South that there was a huge surge coming down the coast.

After leaving school at 15 years of age I worked first as a groundsman’s assistant at the Gore Court cricket ground and then went to Bowater's paper mill and learnt how to make paper. I noticed some of the old men walking in to work on the night shift had been doing it for so long they didn’t have to look where they were going. I thought ‘Do I really want to be doing this for the next God knows how many years?’ National service was still in being and I didn’t particularly want to join the Army for two years… so in 1957 I joined the Royal Navy, you had to sign on for at least nine years. (As it turned out the main National Service finished as I joined!) I don’t regret it and I had a very interesting career and travelled the world, but that meant ‘old Teynham’ and me were to part. I was never to go back and actually live there again and in the mean time it changed almost beyond recognition, but that’s the way it is, nothing stays the same for ever.

Barry Knell