The 1861 Teynham Rail Accident

It was reported in the South Eastern Gazette of the day, that following another railway accident at Sittingbourne the previous day, a more serious accident occurred to the last down train on the evening of Saturday 5th January 1861 about half a mile west of Teynham station.

It was said that the train was made up of an engine, named the “Eclipse” and stated to be, “a very large and powerful one” a tender, five passenger carriages and a brake van for the guard.

The passenger train, the last from London that day, started from Victoria Station punctually at 7.45pm heading towards Canterbury via Chatham and Faversham. The engine was driven by an experienced driver named Maddison, who had been in the employ of the company some time. It left Sittingbourne at its correct time of 9.58pm to travel to Teynham.

As the line was straight, with only a slight gradient, the station master at Teynham was generally able to see the train coming, from his platform, by its lights. However whilst he was watching the train at his usual time, he “suddenly missed it.” Fearing that something serious must have happened, he ran up the line towards it where he met the guard, who was coming to the station for assistance.

A short distance from the station, as the train was going over a level crossing, the engine, by some means or other left the rails, dragging with it the tender and the carriages with the exception of the last.

The engine was found lying in a field on the north of the line some little distance from the rails, partly turned over on its back with its funnel end pointing towards Faversham. Its leading wheels had been left a short distance behind it embedded in the soil. The tender was lying, wheels uppermost, with its leading end also towards Faversham in front of the leading wheels of the engine, beside the down line but on the south of it.

The first two carriages had been thrown to the south of the tender and in front of it and the three others, with the brake van, were behind it and were lying partly in the ditch north of the line. One of the latter was completely destroyed. The first-class carriage was in a shattered condition held together only by its framing at one end.

Fortunately, owing to the lateness of the hour, there were only two passengers in the train, who happened to be in the last carriages; the consequences of the accident would have otherwise been even more dreadful. One of the passengers was a clergyman on his way to Teynham and the other, travelling third-class, was said to be a sailor from Woolwich Arsenal going to Canterbury. They escaped with comparatively little injury, as did a clerk and a porter, employed by the company, who were also travelling on the train.

The driver and two firemen, who were riding on the engine, were either injured or lost their lives either by being thrown or by jumping from the engine when it separated from its tender. Maddison, the driver, was found under the engine, alive but frightfully mutilated. About three hours after the accident, Plested, the fireman, was taken from under a second-class carriage, dead. The third man, in addition to the regular driver and fireman, was a fireman named Hogdon who had been transferred on the 3rd December from Faversham to London, and who was coming down to Faversham with the intention of taking his wife back with him to their new quarters on the following Monday morning. He had been riding from London in one of the carriages, but it appears had got out onto the engine at Sittingbourne station. He was also found dead under the same carriage as Plested.

The guard, who was riding in his van at the tail of the train, did not realise that there was anything wrong until after he had rounded the curve and come in sight of the station lights. He then suddenly felt his van oscillating and jumping and at once began to screw on his brake. Whilst he was doing so, he was struck down, and rendered unconscious. He did not know how he got out of his brake-van; but when he recovered his senses he found himself’ lying in the intermediate space between the two sets of rails, hurt about the back and head. He went for assistance, meeting the station-master.

From about 150ft (45m) from where the train left the track, on the outer side of the rails, the ballast appeared to have been regularly and violently struck by some iron object every 15ft (4.5m) to the scene of the accident. On the uppermost side of the engine the iron rod running from the horn plates, used to mount the axles, was severed along with the horn plates themselves. This possibly freed the axle so that it hung down and struck the ballast as described above. There was no evidence to show if the engine had been thrown off by any obstruction on the tracks and nothing else to account state of the ballast on one side only. The cause of the accident was reported as a mystery and would be fully investigated at the inquest.

The bodies of the unfortunate men were carried to the Railway Tavern Inn, along with Maddison. Immediately upon learning of the accident, Mr. Finnigan, the Railway Company Manager, proceeded from Chatham to Teynham by special train, taking with him a numerous party of labourers who were employed the whole of Sunday in clearing the line.

Below we will cover the Inquest and the Board of Trade accident enquiry. The above article was adapted from newspaper reports of the time.

Go to top

What follows is a contemporary report of the inquest into the tragedy, which was held just three days after the accident at The Railway Tavern, Lower Road, Teynham.

The engine-driver, Maddison, who was so badly injured by the appalling accident which took place on the London, Chatham, and Dover Railway, at a short distance from Teynham station, on Saturday 5th January 1861, deteriorated and died early on Monday morning, the third person killed through this accident.

An inquest on the bodies of Maddison and the two firemen, Edward Ogden and James Plested, was opened at the Railway Tavern on Tuesday morning, 8th January 1861, before T Hills, Esq, Coroner. Mr Cobb, Mr Hilton, and Mr Lake, three of the directors of the train company, were present during the inquiry, as well as Mr Finnigan, general manager, Mr Martley, locomotive superintendent, together with Mr J Cubitt, chief engineer.

The coroner and jury first visited the scene of the accident. The large and powerful engine, which had been turned over into the adjoining field, had been raised and was standing by the side of the line. It was a complete wreck, the front wheels having been torn off, and the engine itself twisted and torn in an astonishing manner. The carriages were all destroyed. Only one of the seats of the 1st class carriage was distinguishable, every other part said to have been smashed to atoms. The jury also viewed the bodies of the unfortunate men, and the following evidence was then taken:

John Goodyear, the guard, said the train proceeded safely until approaching Teynham. The first thing he felt was the carriages jumping. He then applied his brake as he thought there was something wrong. After that he could remember nothing. George Birch, a train porter, said he was in the last 2nd class carriage when it suddenly turned partly over. He said there was no notice whatever given of the accident.

Passenger Patrick May, a practical engineer residing at Ospringe Road, near Faversham, said. “I found there was an unusual oscillation the whole distance I had travelled, greater than I had ever previously noticed. The carriage left the rails, and turned over partly on its side, and after going about 30 yards it came to a stand. I got out of the window, but could see nothing on account of the steam. I saw Ogden lying dead and concluded that all the passengers were killed. I know nothing more about the accident.”

The Rev Robert Antram Keddle, curate of Baddlesmere, who had marks of injuries about the face, said he was a 2nd class passenger in the train which met with the accident and the only passenger in the carriage. “As we approached Teynham I heard an unaccountable sound. I was rather frightened, as I thought there was going to be an accident and caught hold of the side of the sash of the window. The carriage shook violently once or twice, and I was dashed up against the window. There was a tremendous crash. As soon as I could I got out, when I found that the carriages were a heap of ruins.”

Mr Stephen Williams, station-master at Teynham, said that missing the head-light of the train, and hearing a great noise of steam, he ran towards it, and found the wreck before described. On searching about, he first found the engine-driver, who said he was not seriously hurt, and with a little assistance he thought he could get up. After telegraphing to Faversham for assistance, witness returned and found the two deceased, Ogden and Plested. Witness walked up the line, and saw the piece of iron now shown to the jury which formed one of the horn plates off the front of the engine.

Before his death the engine-driver told witnesses he could not make it out at all, as the train was coming along very nicely; he had felt a sudden jerk, and could remember nothing more.

Mr William Martley, the locomotive superintendent belonging to the company, deposed: “The piece of iron shown to the jury formed the leading horn of the left-hand frame of the engine. That protects the fore-wheels and keeps them in their place. When it became broken, the effect would be the wheels would be thrown off the line. I have no doubt that the want of this horn-plate was the cause of the accident.”

The Coroner asked the witness if he could speak on the quality of the iron of which the plate was manufactured. Mr Martley said the break showed faults in the iron, but he could not tell whether or not they were old breaks. There was no doubt that the fault existed before the breakage which caused the accident, but for how long before he could not say. He said that the quality of the iron was not first-rate and did not think the horn would have broken unless it had received some unusual impact. He suggested that the present frosty weather had an effect upon the metals, making them more brittle. He thought that some foreign object must have struck the horn, but although he had searched on the line he had not been able to discover anything.

He said the engine had been thoroughly examined by the company’s foreman on the previous Tuesday, but no sign of a crack was observed. The other horn-plate was subjected to rougher treatment than that which broke, but held better.

He said he had visited the engine driver before his death, and he told him that he thoroughly examined the engine before leaving London, again at Sittingbourne and could not find anything wrong.

Mr Thomas Aveling, agricultural engineer, Rochester, stated that he had seen a great deal worse iron than that produced. “The iron was short-grained, and the flaw in it, which was of old date, made it look much worse than it otherwise would. There was no doubt the cold weather helped to break it, looking at the state of the iron, but he should not have been surprised if it had broken before.”

The Coroner remarked that there did not appear to be any want of care and, besides, the fracture would not be visible as it was covered with paint and grease. He said there was no doubt the cold weather affected iron, but there was no ground for the suggestion that anything had been placed on the rails maliciously. If the jury, looking at all the facts, were of opinion that the occurrence was caused by accident, they should return a verdict to that effect and append any remarks they may wish to it.

The jury then deliberated for a few minutes and handed in a verdict of “accidental death, from the breaking of the horn plate of the engine; but how it was caused there was no evidence to show.”

The above was adapted from newspaper reports of the time. Below we bring you the Board of Trade’s report into the accident, which comes to a strikingly different conclusion.

Go to top

Above we reported a tragic railway accident which happened outside Teynham station in 1861 and killed three men. The following is extracted from the Board of Trade report given by Capt (RE) H. W. Tyler, The Secretary of the Rail Department, Board of Trade, Whitehall, on 19th February 1861. As you will see, Capt Tyler pulled no punches with his conclusion.

The 7.46 pm passenger train started from Victoria Station in London punctually on the day in question for Faversham, and left Sittingbourne, which is rather more than 46 miles from London, also at its proper time - 9.58 pm. It consisted of an engine (the Eclipse) and tender, five carriages, and a brake-van, and was due to travel between Sittingbourne and Teynham, a distance of 8.1 miles (including the stoppage at Teynham), in 8 minutes. If 3 minutes be allowed for time lost in getting up speed after starting from Sittingbourne, and in reducing it for stopping at Teynham, and if 1 minute be deducted for detention at the latter station, there are then only 4 minutes left for the journey between the two stations and this would represent a maximum running speed of more than 54 miles an hour. There is, therefore, hardly enough time allowed between these stations; but it does not appear that a high speed was employed on this occasion and it is stated that, as the train approached Teynham, the speed did not exceed 20 miles an hour.

The line was straight; the gradient a rising 1 in 660. The station master saw the train coming, by its lights, at the usual time. But whilst he was watching he “suddenly missed it.” He feared that something serious must have happened, and ran up the line towards it. He met the guard, who was coming to the station for assistance, and found it in the following condition:

‘The engine was lying in a field on the north of the line, at some little distance from the rails, partly turned over on its back. Its funnel end pointed towards Faversham, and its driving and trailing wheels, which were in their places, were towards the northwest. Its leading wheels had been left 10 or 12 yards behind it, and were embedded in the soil. The tender was lying, wheels uppermost, but with its leading end also towards Faversham, 20 yards in front of the leading wheels of the engine, by the side of the down line, but on the south of it. The first two of the carriages had been thrown to the south of the tender and the three others, with the van, were behind it and lying partly in the ditch on the north of the line. One of the latter was completely destroyed, and one of the former - a first-class carriage -so nearly so, that the framing and one end of it only held together, in a shattered condition.”

There were, fortunately, only two passengers in the train, of whom one was a clergyman, and the other a third-class passenger from Woolwich Arsenal. They escaped, as well as a clerk and porter in the service of the company, who were also travelling by it, with comparatively little injury. But the driver and two firemen, who were riding on the engine, all lost their lives, either in being thrown, or in jumping from the engine, when it separated from its tender.

The third man, in addition to the regular driver and fireman, was a fireman who had been moved from Faversham to London, and was coming down to Faversham with the intention of taking his wife back with him to their new quarters the following Monday morning. These men were lying partly under the carriages, and were probably run over by them, after falling from the engine.

The guard, who was riding in his van at the tail of the train, did not perceive that there was anything wrong until after he had rounded the curve to the west of Teynham, and come in sight of the station lights. He then suddenly felt his van oscillating and jumping, and he at once began to screw on his brake. Whilst he was doing so he was struck down, and rendered unconscious. He does not know how he got out of his brake-van; but when he recovered his senses he found himself lying in the intermediate space between the two lines of rails, much hurt about the back and head. He went forward for assistance, and met the station-master, as I have stated.

When the permanent way was examined after the accident, a portion of the horn-plate of the engine was found lying close to a level-crossing, 700 yards [640 metres] to the west of the Teynham station: and there was a hole in the ballast, as if from something having been forced violently into it when this portion of the horn-plate was thrown off.

The whole affair had happened within a very short space, both of time and distance, and the stoppage of the train was sufficiently sudden to account for the violent effects which were produced, without its being necessary to suppose that extraordinary speed was employed. A great deal of injury was done to the permanent way. It was found necessary to insert 5 new sleepers, 52 intermediate chairs, and 4 joint chairs, in place of those which were damaged or broken in the course of the accident, besides two new rails, to replace those which were bent when the engine left the line.

The portion of hornplate thus discovered was found to belong to the part of the engine immediately behind the left leading axle-box. It is of the utmost importance that hornplates should be carefully constructed, of suitable form and dimensions, and of good material.

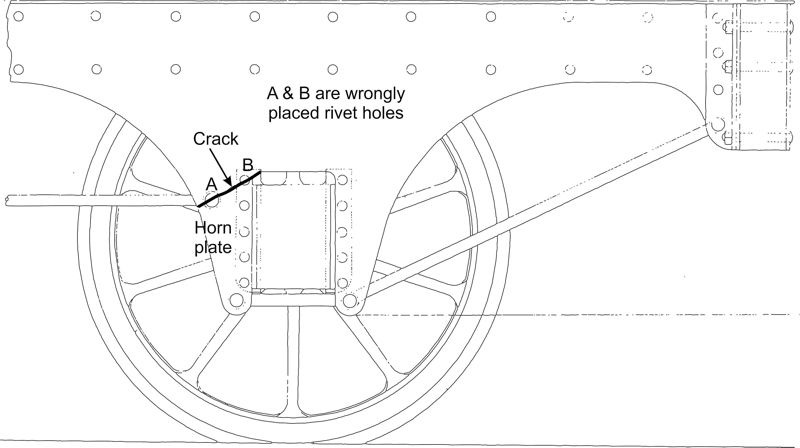

In the present instance these conditions were not complied with, and failure has resulted, partly from defective construction, and still more in consequence of the employment of material of very bad quality. The material, indeed, was such as ought not to have been purchased by an engine-builder at all; and that it should have been thus employed in this engine is most discreditable to the firm that sent it out for use. The construction was also defective with a rivet-hole wrongly positioned and the thickness of the plate used in this instance was only three-eighths of an inch.

The ‘Eclipse’ was a six-wheeled engine, with six rear driving wheels, and was supposed to weigh six tons. It had been purchased by the company, ready made, from Messrs Hawthorn of Newcastle, in August last, and had been constructed by them, apparently, either for some foreign line or for other parties in this country. It was found, after the accident, that the corresponding horn on the right side of the engine had given way, and was only hanging on to the plate; that both of the portions of the horn-plate in front of the leading axle-boxes (or rather of the positions which they had occupied) were cracked; and that the hinder horn of the left trailing axle was also cracked.

The ‘Eclipse’ was a six-wheeled engine, with six rear driving wheels, and was supposed to weigh six tons. It had been purchased by the company, ready made, from Messrs Hawthorn of Newcastle, in August last, and had been constructed by them, apparently, either for some foreign line or for other parties in this country. It was found, after the accident, that the corresponding horn on the right side of the engine had given way, and was only hanging on to the plate; that both of the portions of the horn-plate in front of the leading axle-boxes (or rather of the positions which they had occupied) were cracked; and that the hinder horn of the left trailing axle was also cracked.

From the appearance of the portion that fell off the engine, I should say that its partial fracture ought certainly to have been observable for at least some days before the accident. But it is stated not to have been seen; and the evidence of the man who would have been principally responsible for observing it, the driver of the engine, cannot now be obtained.

This melancholy accident, which has caused the death of three persons, and which would, if the train had been a full instead of nearly an empty one, have undoubtedly been fatal also to a number of passengers, is due to the employment of material of bad quality in a careless manner, and is one which would, with proper supervision and ordinary care and prudence, on the part of those who constructed the engine, have been avoided.

Compiled from reports of the day by

Cllrs Tony Rickson and Brian Sharman

Go to top